The Robot Apocalypse Has Been Canceled

But Even if It's Not, that Probably Wouldn't be so Bad

In this post:

Signal Flares & Trendlines

The Story of The Story of Frankenstein

Becoming Human

Re-Becoming Human

Life After Robots

Canceling The Robot Apocalypse

I got a feeling: the robots are coming. Not like my usual 'the robots are coming' feeling, but something more acute. To keep my paranoia in check, I deployed all my usual techniques: Separating Inner and Outer Assumptions, A/B testing them all, watching the trendlines, looking for signal flares when they're still low in the sky. There were a few things that really stood out:

SIGNAL FLARES & TRENDLINES

Signal Flares:

Signal Flare 1: Figure Robotics partners with OpenAI:

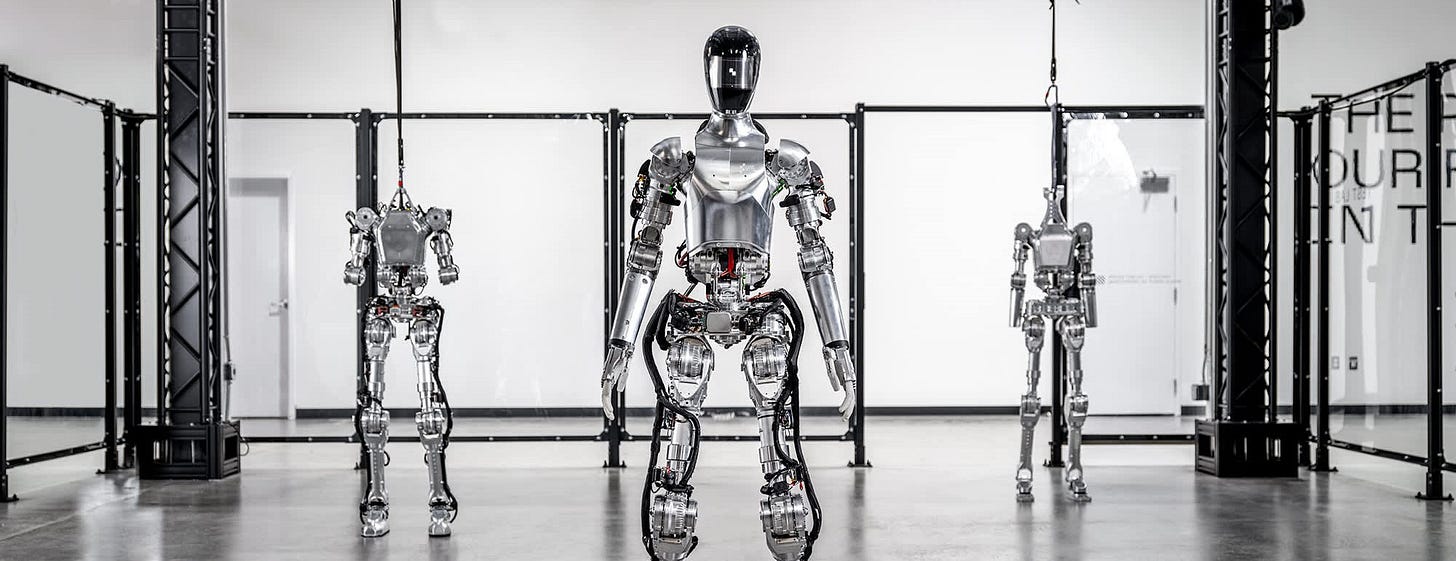

Last week, Figure Robotics announced a partnership with OpenAI. It was inevitable that someone was going to put an LLM into a robot. In fact, several companies are doing so. Why is it significant that this robotics company forms a partnership with this AI company? See Signal Flare 2.

Signal Flare 2: A Bunch of Really Rich People Just Poured Money into One Particular Robot Startup (hint: It’s Figure):

There's lots of different robot startups, all seemingly in a horse race to debut the first commercially viable general purpose humanoid robot. If you wanted in on the action, the best investment strategy would be to spread your money around, so that you'd be covered, regardless of which robot company eventually won the race. The only reason to put all your money on one horse, or for everyone to put their money on one horse, would be if the race were fixed, or if it were already over. Last week, Figure Robotics announced a new $675M funding round detailing investments by Microsoft, OpenAI's startup fund, Nvidia and Jeff Bezos. The fact that so many tech titans now seem to be gathering around this one company seems significant, especially when viewed against the backdrop of its partnership with OpenAI.

Signal Flare 3: Elon Musk Just Filed a Massive Lawsuit to try and stop OpenAI's Progress:

Also last week, Elon Musk filed this lawsuit, ostensibly to stop OpenAI from developing AGI, because, according to the suit, the organization had abandoned its nonprofit mission. I won’t write too much about it, because new details are surfacing every day. But suffice to say, this is the kind of lawsuit you file when you realize that you’ve lost the race, in order to give your company a chance to catch up.

Signal Flare 4: These Tweets:

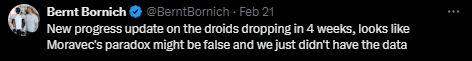

Robotics engineers aren't immune from giddiness or excitement, or letting the cat out of the bag. In the last few weeks, robotics twitter has been buzzy, as if something is about to happen. Most compelling was this tweet from Bernt Bornich, CEO and Founder of robotics company 1X Technologies:

Moravec's Paradox is the general idea in AI and robotics that robots will find it hard to do the things that humans easily (like picking up a coffee cup). And humans find it difficult to do the things that machines do easily (like advanced mathematics). That's because reasoning, as it turns out, doesn't require a lot of computational resources, while perception and sensorimotor coordination actually do. That’s always been gospel. But if it were wrong, it would mean that someone has figured out the easy way to program perception and sensorimotor coordination, which means the trending improvement in robot eyes and brains may have arrived at its destination . . .

Trendlines

Trend 1: All The Technologies Needed to Make a Robot Have Caught Up:

The challenge of building humanoid robots was never in the body – it was in the brain. It’s comparatively easy to build a humanoid robot and then pre-program a bunch of things for it to do, especially if you limit its environment to a known, wide open, flat space (e.g. a warehouse). But to be a general-purpose robot, a robot needs a brain - one that can learn. To learn, it needs to be able to see, and communicate. These technologies (learning, seeing, communicating) have rapidly advanced in the last 24 months, so much so that it seems that a humanoid, general-purpose robot might already be here.

Seeing:

A general-purpose humanoid robot would need to be able to see the world the way we do, and computer vision has proven a stubborn problem to crack. Mounting a video camera on the head of a robot won’t get you to human vision. To approximate human vision, a robot needs to be able to 'segment' - the ability to look at a white sheet of paper on a white desk and recognize that it’s a sheet of white paper on a white desk, as opposed to a white desk with a rectangle drawn on it, or something like that. Human vision separates the world into objects and establishes relationships between them. It would also need other features of human cognition, such as:

Object permanence: When the white sheet of paper is put into a drawer in the desk, the machine must understand that the piece of paper still exists.

Continuity: When the piece of paper is blown off the desk, it will flutter gently down to the ground, and there it will stay until it is moved by another object or force.

SORA seems to have solved these problems. Or, more precisely, the methods which OpenAI used to train SORA will solve this problem. SORA's training is essentially a loop: it observes something, tries to replicate it, is evaluated, and then refines its approach. Since SORA was trained on video, it developed an internal, spontaneous understanding of the physical world and how it works. SORA sees exclusively through video - a two-dimensional representation of the world. But it thinks in a dynamic, four-dimensional way. That's exactly the kind of thinking a humanoid robot needs to have.

Learning:

In a recent demo, the Figure robot showed that it had learned to make a cup of coffee – after only ten hours of training. Such slow learning would be intolerable for any general-purpose robot, because any time the robot encountered a novel condition, it would have to be sent back to the factory in order to learn how to do that thing. There's no way to preprogram a robot for everything that it might encounter - it needs a way to figure things out, on the fly and in the field.

Because of the manner in which SORA was trained to create videos, we can easily imagine a robot learning from its own mistakes by watching itself make them. It needn't necessarily train on how to load a dishwasher by watching humans load a dishwasher. As long as it understands what those words mean, it could try it on its own, fail repeatedly, and gradually acquire the knowledge to load a dishwasher. But it likely won’t need to - it can sync learning across armies of itself. You wouldn’t need 1 robot to practice loading a dishwasher 1,000 times if you had 1,000 robots all learning in their own environments and sharing that learning with each other. New techniques such as Any-Point Trajectory Modeling even demonstrate how robots can teach other, dissimilar robots how to perform the same task.

In that way, physical robots represent an entirely new form of learning, because they represent an entirely new form of information gathering (at least for A.I.). A physical robot can touch, feel, make mistakes, and assimilate knowledge from those experiences. And they can subsequently share this knowledge instantly with each other.

Communication:

Finally, general purpose humanoid robots would need to be able to communicate in natural language in order to ask questions, accept instructions, etc. Imagine that every time you wanted your robot to do something new, you had to hook it up to a laptop and write new code. That would be practically useless! GPT 4, along with a natural language interface like Whisper (which OpenAI already owns), solves this problem instantly. A robot could receive instruction via normal human language and internalize that into whatever internal coding system it was operating on.

Trend 2: The Cost Has Come Down by a LOT

The recently unveiled Unitree H1 lists at $90,000 USD, a steep price for a household toy, to be sure. But if Amazon wants to replace a human warehouse worker, it makes morbid financial sense:

Currently, an Amazon warehouse worker in California makes $17.34/hour to do backbreaking work. Assuming roughly 2,000 working hours per year, that worker will take home $34,680 per year. Assuming 50% OH&B, that employee will cost Amazon roughly $52,000 per year, or roughly $26 for every productive hour.

A Unitree H1 will have double the upfront cost, but can work 24/7/365. Even taking out 20% of the robot’s time for charging and repairs and such, it can still work 7,000 hours per year, or roughly $12.80 for every productive hour. And Amazon no longer has to worry about labor codes, or HR, or strikes, etc.

To be clear, I’m not arguing that widespread human labor replacement is a good thing. I’m only observing that as the price comes down, such a result trends towards inevitable.

THE STORY of the STORY of FRANKENSTEIN

I think you add all this up, and you can only draw one conclusion. Figure Robotics has worked it out. They have a commercially viable, intelligent, humanoid, general purpose robot that's ready to go to market in the very near future. So what happens next? My guess is that it will lack the fanfare that we're typically shown in movies, where hundreds of thousands of robots are bestowed on humanity at once, every child gets their own robot for their birthday, and eventually the robots turn evil and try to kill us. It’s tough to say what will happen, but here are some guardrails:

Form, Not Being

Robots will first go to wherever they're most useful, and a humanoid robot will be most useful where the human form is necessary to execute a particular task or serve a particular function, but a human being isn't. It will begin slowly. This particular product rollout has not only financial implications, but world-changing economic, social, military and existential consequences as well. Big Tech will want to release a few into the wild, at first, where they can start to figure out what the bugs are. If someone figures out how to hack one, and make it into a murderbot, it would be much better to have 25,000 murderbots on the loose than 25,000,000.

Early adopters will be special use cases. Got a radiation leak in your nuclear power plant? Send in the robot. That will flush out the really mundane bugs (e.g. the robot is afraid of small rodents).

From there, the circle will widen, and we'll see robots showing up more and more in different work and social roles. For the conceivable future, it will largely be in places where some other kind of robot couldn't do the job better. It wouldn't make a ton of sense to have your humanoid robot driving a truck, full-time, because there are much easier ways to get trucks to drive themselves.

The Story of Frankenstein

As robots become more ubiquitous, we'll be writing a new chapter in human history. It'll read a lot like Frankenstein, sorta. The first half will read like the Story of Frankenstein. The second half will read like the story of the Story of Frankenstein. We'll go through the following phases:

Excitement:

The moment when Victor Frankenstein screamed "It's aliiiivvvvvee"? The whole world is going to shout, "Holy shit, we've got robots." Hell, I still get that feeling every time I see a self-driving car.

Repulsion:

The horror and disgust that Victor Frankenstein felt when finally realizing what he had created. Yeah, we're going to have that too. The good feelings will give way to bad ones. People will realize that these robots are going to take their jobs. People will resent the comparative coldness of a robot traffic guard at their children's school. Their resentment will grow as different parts of the human world are reshaped for the benefit of robots.

Revenge:

Frankenstein’s Monster destroys Victor's life, and so Victor pursues his own creation into the Arctic in order to destroy it. Robots will destroy some people's livelihoods, sense of normalcy, and security, so people will want to destroy them.

The Story of the Story of Frankenstein

Here's where the story turns, though. The story of The Story of Frankenstein is a story of acceptance and widespread prosperity.

Shelley wrote Frankenstein as a critique on the Enlightenment's emphasis on reason, a parable about the dangers of maniacal pursuit of scientific progress and the hubris of trying to overcome the natural order. We continue to celebrate the book, and its lessons are evergreen, to be sure. But they were lessons we largely ignored. In the 200 years since, we've continued to maniacally, relentlessly pursue technological progress, including various means to transcend death, just like Victor Frankenstein. It gave us vaccines, and space travel, and extremely long lives (relative to Mary Shelley's time). Sure, it gave us H-bombs, and social media, too. But we are still here, and life is better than it was 200 years ago, for everyone.

BECOMING HUMAN

The waves of repulsion, anger, disgust, protest will subside as we evolve to meet this new paradigm. Our understanding of what it means to be human will evolve. Indeed, it has always done so.

At one point, humans believed that they lived at the center of the Universe, and therefore at the center of God's favor. Then a few crazies came along and said 'urrrr. . . . no.' Does that mean that humans aren't the center of God's attention?!? It was such a bothersome question that it took the Catholic Church 250 years to admit the Earth orbited the sun. But, we got over it. We're not the center of the universe, but we're still pretty awesome.

At one point, humans believed that they were the point of evolution. Darwin wasn’t the first to propose the idea that some species might turn into others (Anaximander) or even the first to propose that humans might be descended from apes (Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, as well as Thomas Henry Huxley). Darwin's thought-crime was proposing the system of natural selection, meaning that species evolved on an ongoing basis. Humans, as they existed in 1871, were not the creation of God or anyone else, because they weren't even finished. But, we got over it. We're not the intended end result of evolution, but we're still pretty awesome.

At one point, humans believed that they were the only animals that use tools. Then Jane Goodall helped us figure out that primates do, too. Also, birds, octopi, otters, and so on. We got over it. We're not the only ones that can use (or make) tools, but we're still pretty awesome.

At one point, humans believed that being 'human' was defined by being able to communicate. Then other naturalists and newer technology helped us figure out that all animals do that. Dolphins give each other specific names. Cows even have regional accents. We got over that, too. We're not the only animals that communicate, but we're still pretty awesome.

RE-BECOMING HUMAN

‘Getting over it' takes time, however. In the arms of our parents, we all begin our lives as the most important person in the world. And we never stop yearning for that. We seek out partners, and friends, and jobs that make us feel special, and important, and wanted. Humanity, writ large, has gone through the same struggle - wanting to feel important, special, and not as if we're just the result of a bunch of space dust that whirled around in a random, very fortunate way.

The ongoing process of 'de-centering' humanity in the cosmos has taken place over centuries. Mercifully, we've always found some way to re-validate ourselves.

We began a similar struggle when ChatGPT was released in November of 2022. Its early form was enough to kindle that ancient instinct "What if what we thought made us special isn't so special” ChatGPT could converse. It could tell jokes. It could solve basic problems. It seemed eerily human.

That's also probably the reason that the professional managerial class (including architects) had such a visceral reaction to it. Ours is a world that is dominated by words, mostly written on, and sent over, computers. It's our ability to navigate that world that gives us status, and income, and self-esteem, and meaning.

But we weren't yet hit with the full-blown existential crisis that Victor Frankenstein might have endured. As impressive as ChatGPT is, at its debut it was just a Chatbot. We drew psycho-social comfort in pointing out what it couldn't do:

Sure, ChatGPT seemed smart, but 'at least it can't remember more than 3 pages of text at a time.'

Sure, Midjourney might be impressive, but we comforted ourselves with the idea that 'at least it can't draw hands.'

Very rapidly, we've seen AI progress to do things that we said it couldn't do. LLMs started remembering hundreds of pages at a time, and perfectly. Midjourney started drawing hands.

And throughout this progression, these artificial intelligences even started to seem more human, even outperforming humans on emotional tests.

They even imitates our foibles, which we learned when OpenAI confirmed that ChatGPT was getting lazier and prone to slacking off.

AI is terrifying, and infuriating, because it continually invades the space defined by what we thought humanity was. Robots are going to advance this invasion over yet another frontier, granting AI access another, unprecedented territory: our non-digital world.

LIFE AFTER ROBOTS

Robots will present a psycho-social challenge because it will be another way in which we feel less special than we were yesterday. Or, maybe, we have to confront the fact that what made us special was not just having opposable thumbs and being able to stock a warehouse. We must recommit, in our time, to that journey that contemporaries of Copernicus and Darwin began: we must refine our definition of what it means to be human.

Robots represent an unnerving penetration into our realm - the realm of the physical.

For all the amazing things that ChatGPT, Midjourney et al can do, they can't 'escape the computer.' They're trapped there. We can always turn off our computers and go outside. It's a curious inversion of the nightmarish prison for humans depicted in The Matrix. In that film, machines trapped humans in the digital world so that they could exploit them for energy. To be liberated was to leave the 'prison of the mind’ and join the 'real' physical world (although that world looked pretty shitty, IMHO). AI has been in a prison of the digital. Its actions might have had 'real world' consequences, but it could not physically enter or manipulate our physical world. That’s all about to change.

CANCELING the ROBOT APOCALYPSE

Don't worry, there won't be a Robot Apocalypse. But even if there was, that might be okay. The word 'Apocalypse' gets a bad rap. In contemporary usage, it’s taken on sinister meanings - the end of all things, a time of torment and suffering. It's originally derived from the Greek word "ἀποκάλυψις" (apokálypsis), which means "uncovering" or "revelation” or “to pull the lid off of something.” Which is probably how it got conflated with the depictions found in The Book of Revelation of the New Testament. The Book of Revelation likely got its name because there was an uncovering. It was the final act in a long human story, where the point of all this drama is revealed. It is, in a weird way, a happy ending. Because God has brought eternal paradise to all of his followers and brought justice to all the wicked. All the little details of the plan that we puny humans couldn’t understand along the way are explained, and sense is made of our suffering. 'Apocalypse' - either in the Greek or Christian construction, is about transcendence. It's about destroying or abandoning what is in favor or something higher, or better. And that's what I think the widescale deployment of robots will ultimately give us: transcendence. We will move beyond our current definitions of what it means to be human, into something else, just like we always have.