The Crumbling Foundations of Architecture

How Recent Employment Data Demands New Ideas on How We Train Future Architects

In this Post:

No Easy Toeholds Left

Could This Trend Not Continue?

Termite Colonies Only Grow in One Direction: Outward

A Fundamental Restructuring of Unknown Form

Disaster experts are the only people I know who actually want to be wrong. Other people will say things like ‘I hope I’m wrong about this, but . . .’ It’s almost always a lie. No one likes being wrong. It’s embarrassing. And annoying. But disaster experts very, truly, chronically hope to be proved wrong.

I hoped I was wrong when I gave a presentation at the AIASF Design Technology Conference on the future of Design Education in Feb. 2024 and described what I then referred to as ‘The Pipeline Problem.’ It shall hereafter be known as ‘The Termite Problem’, but more on that in a bit.

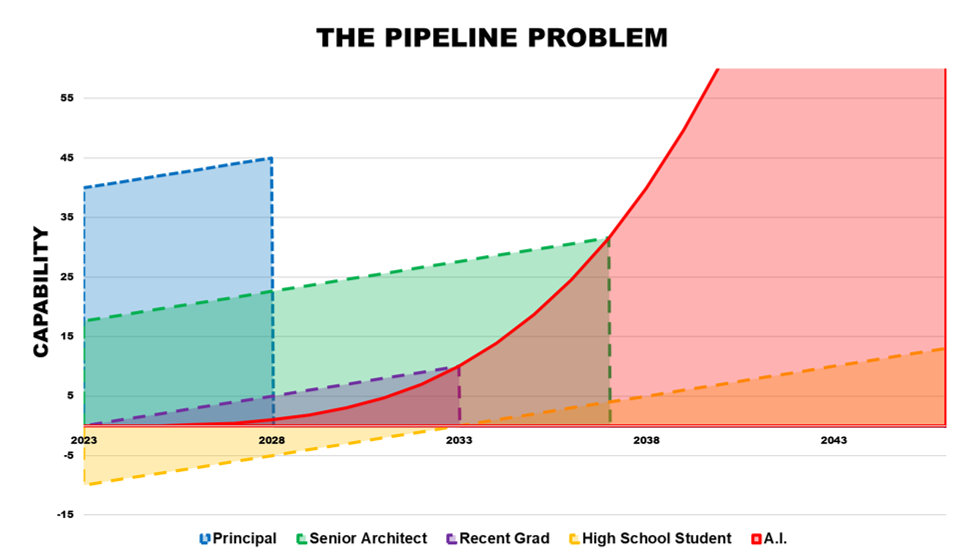

It went like this: AI learns exponentially, while humans learn linearly. Whatever you think AI knows or can do now isn’t so important as what it will be able to do in the future. And in the future, things that grow exponentially always catch up with things that grow linearly, no matter how far behind they seem today.

The more senior & experienced you are as an architect, the less this matters, because it will take AI longer to catch up with your capabilities. But for junior architects, and architecture students, it presents a clear and present danger. The work that a first year architect does is typically rote & mechanical (at least, mine was). You’re learning. And you gotta walk before you can fly. But that’s exactly the kind of work that AI is good at now. That creates a strong incentive for firms to not hire young architects and adopt AI instead. That creates a strong disincentive for young people to even pursue architecture in the first place. If you’re 17, and considering going off to school to study architecture, why would you spend 10 years learning a craft when you have no ability to even imagine what AI will be capable of in ten years’ time? Why take the AREs? Why do any of it? AI capability is doubling every 7 months over the last six years; if that trend continues, AI will improve by 1,000,000x over the next six years. How do you even begin to evaluate what an AI that’s one million times more powerful than our current systems is capable of doing, architecturally speaking? You don’t. You turn away from architecture into other disciplines that seem like they would be more ‘AI proof.’ That leaves architecture with no rising generation, eliminates the early-career experiences on which design judgment is built, and fractures all existing mechanisms of professional development.

I had really hoped I was wrong. But a new study from Stanford suggests my fears were not unfounded.

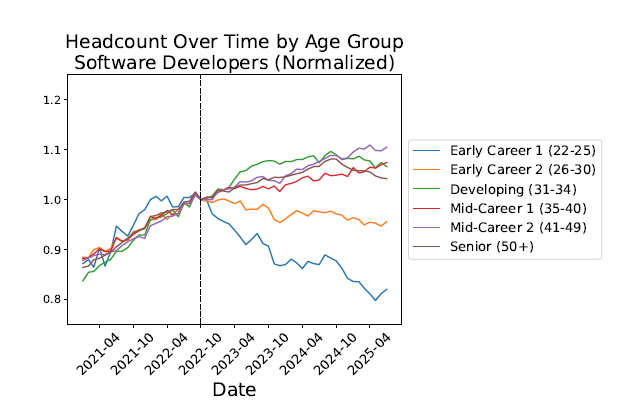

Canaries in the Coal Mine? Six Facts about the Recent Employment Effects of Artificial Intelligence, a joint study from ADP (the payroll people) and Stanford, details how AI is already reshaping the labor market. Their headline finding: entry-level jobs are starting to evaporate in occupations most exposed to AI. Software developers aged 22-25 have seen employment drop nearly 20% since late 2022. Customer service roles show similar declines. Meanwhile, employment for older workers in the same fields continues to grow.

Translation: it’s not that we need fewer coders, generally. It’s just that we fewer junior coders.

The authors are careful in their conclusions. They note that mid- and senior-level workers seem insulated, at least for now. Tacit knowledge, accumulated judgment, political acumen - all supposedly make these jobs harder for AI to touch.

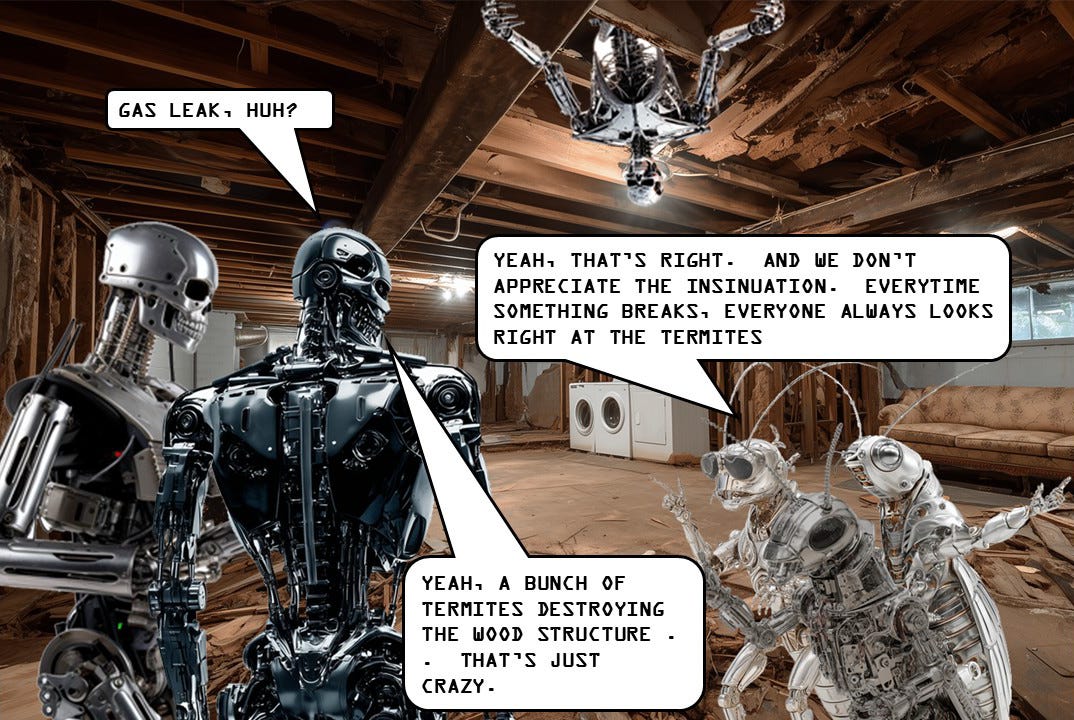

But I’m not convinced. The researchers call the younger workers in this study "canaries in the coal mine." But I think they’re more like termites in the foundation. We sacrifice a canary’s life so that miners can live to mine another day, in another mine. The dead canary doesn’t even strike us as a loss.

Termites in your foundation, however, tell you that something has already been destroyed, and you’re on your way to further destruction, unless you do something dramatic. If you have termites in your foundation, you treat it as a certainty that next month, they’ll be in the first floor framing, the month after that, the 2nd floor, and so on, and so forth. That kind of progression seems curiously undiscussed in the paper: if AI is already replacing entry-level knowledge work, and AI is growing in its capabilities, why wouldn’t mid-level knowledge work be next?

The researchers tip toe around this question like the termites’ intentions were unknown. Of course the termites will spread – that’s in their nature. As it is in the nature of AI to expand in capability, the more its used. Every time a mid or senior architect uses AI to solve a problem or answer a question, they're teaching that AI. Every solution becomes data – even the ones the AI gets wrong. Every workaround becomes a pattern. As with termites, there is no future scenario where AI just stops growing on its own.

No Easy Toeholds Left

Entry-level jobs are the foundation of an architect’s career, metaphorically and literally. Those first jobs are about more than low wages and grunt work. They’re what we build everything else on top of. Those jobs are where you screw up a code check, where you sit through boring client calls, where you make your first presentation deck way too long. That’s how you learn. That’s how you move up.

Now imagine a future where every architect has a foundation rotted through with termites, and is trying to build the higher-level skills of an architect on top of that. Those architects never had a solid foundation to build on, because AI was doing the code checks. AI was doing the boring calls. And AI drafted all the presentations in the background while you weren’t looking. What would a first year architect even do? Do they leapfrog into senior roles without the messy middle? Do we expect them to absorb professional judgment by osmosis?

Without entry-level work as a foundation, building a proper architect seems downright impossible. Doing grunt work, and making mistakes, leads to experience. Experience leads to competence. Competence, properly framed, becomes the kind of wisdom that makes for a great architect – what the authors characterized as ‘tacit knowledge.’

This is the stuff you can't learn from books. The knowing nod when a contractor suggests a particular flashing detail, and you say, "That's going to leak," and they ask how you know, and you just know.

It's knowing which planning official to call when your project gets stuck in bureaucratic quicksand. It's the intuitive understanding that a certain design won't work in practice, even though it looks perfect on screen. It's the accumulated wisdom of a thousand mistakes made and corrected.

It’s a process of training that stretches back millennia, and we’re blithely carrying on while it’s being eaten from the bottom up.

Could This Trend Not Continue?

Let’s be generous for a moment. Under what circumstances would these trends not continue?

Infinite Demand

Maybe AI makes everything so cheap that demand for everything explodes, and employment increases rapidly to fill demand. But that only holds in sectors with infinite elasticity. Architecture, law, medicine - these hit ceilings fast, because the demand for them is constrained by things that grow slow. Every individual only needs a certain amount of legal & medical services. If you make a kidney transplant really cheap, it doesn’t mean everyone will rush out and get one. The number of transplants isn’t driven by their availability or price – it’s driven by the demand for transplants. Similarly, the demand for design services is driven by the demand for buildings, and the demand for buildings scales with population growth, industry growth, immigration, etc. All things that grow rather slowly, relative to technology.Mass Redeployment

Maybe firms retrain displaced workers into new roles. But historically, most firms use automation to cut costs, not create opportunities. That’s what happened in the Industrial Revolution, and the Digital Revolution.Regulation or Cultural Firewalls

Maybe governments ban AI from certain domains. Maybe professions draw hard lines. But guardrails don’t tend to hold when competitive advantage is on the line. Think about every city that’s ever tried to ban Uber in order to protect existing taxi industries. They keep failing because people inherently see the better value in Uber’s tech-enabled platform. Professional domains are defined by the public interest – to keep the public safe. If an AI Doctor can see you faster, and diagnose you better, it would be hard for the AMA to make the case that the public welfare is better served by forcing everyone to see human doctors instead.AI Hits a Wall

Maybe tacit knowledge is harder to replicate than we think. Is there some ceiling beyond which AI can’t develop? Some knowledge practice it can’t emulate? I’m sure there is. But I also know that recent years have been a steady drip of AI Skeptics saying ‘well, AI can’t do ‘X’’ and then AI being able to do ‘X’ a few months later. I’m not sure why anyone would be confident at this point in saying ‘AI will never be able to do ‘Y’’

All of these are possible. None of them feel probable.

Termite Colonies Only Grow in One Direction: Outward

There is a legitimate, present question to address: what are young architects going to do at the firm? But there’s also a broader, more serious issue: the entire progression of professional development is collapsing. In a world where AI eats out the foundation and hollows out the middle floors, what’s left is a bunch of humans stranded on the wobbly roof of, let’s face it, the termites’ house - making “strategic decisions” over outputs they no longer really control. That’s not a profession. That’s just management kayfabe.

If we don’t rethink the pipeline now - we won’t just lose jobs. We’ll lose the process by which architectural expertise is generated.

I would start here:

Rebuild pipelines that assume AI is a co-worker from day one.

Rethink mentorship as more than just passive exposure to senior staff, but actual bi-directional teaching between generations.

Design systems where human learning isn't just a side effect of work, but a strategic function.

Reform architectural education accordingly (more on this in a later post)

A Fundamental Restructuring of Unknown Form

The Stanford study provides valuable data about what's happening now. But it also shows clear evidence of an emerging trend. If the trend holds – if AI continues to spread into new domains, and deepen its knowledge of all of them, if protection of tacit knowledge proves temporary, if entry-level positions continue disappearing – then we're not looking at an adjustment period. We're looking at a fundamental restructuring of how architects become architects.

The canary is clearly deceased. If that were the whole story, there’d be nothing to fear, and nothing to do (save for evacuating the mine). But if it’s termites, then some dramatic action is necessary and urgent.

Let’s not mistake one for the other.