Spatial Computing & the Future of Design

Or, How We Get to Design's Future by Going 5,000 Years in the Past

In this Post:

The History of Ideas: from 4D to 2D

This History of Ideas: from 2D to 1D

The Future of Ideas: from 4D, to 1D, and back to 4D

Spatial Computing: Product Flop or Revolution?

I can't decide whether the release of the Apple Vision Pro is an iPhone moment or Apple Newton moment. It could be either. I don't use the term 'Apple Newton moment' here to describe anything particularly negative, and it's certainly not meant to be derogatory. The Apple Newton was just ahead of its time. It was realized into a world that didn't have the ecosystem (either technological or cultural) to support it. That has seemed to be Apple's specialty all along - they don't create products for the ecosystems of others - they either create their own, or, in rare cases, release a product without one (which subsequently fails).

I think in either case, the release of the Apple Vision Pro is going to be a watershed moment for architects.

And no, I’m not an Apple fanboy. I don’t even use their products. But I think spatial computing must certainly change the way architects practice, because it makes one of architects’ traditional superpowers completely redundant. Much of what architects do (and do better than anyone else) is to shepherd four-dimensional ideas from a four-dimensional world, through a two-dimensional one, and back out again. Taking the long view (I mean, like, the last 5,000 years), that intermediary detour through the two-dimensional world may no longer be necessary. It’s not intrinsic to the process of designing, or building. It has been necessary for the last 5,000 years or so, but there are very specific reasons for that necessity. Reasons which may be at an end.

Because of the Apple Vision Pro (or its successors) and spatial computing (more generally), the ‘flattening’ of our ideas into two dimensions may actually become a hindrance to creativity and progress. To understand why, we have to go waaaayyyyy back:

The History of Ideas: from 4D to 2D

Building Humans

Biologists believe that stereoscopic (3D) vision evolved somewhere during the Cambrian explosion, roughly 540 million years ago, and ever since, anything that wanted to survive had to navigate the world in three dimensions. Human brain evolution had much to do with four-dimensional vision - it's thought that much of humans' brain power evolved in order to be able to throw things (like rocks & spears) at other things (like running gazelles). The acuity with which humans could do so gave them an advantage over other predators that were faster, stronger, and had sharper claws.

Building Civilization

While humans ascended to the top of the food chain through this four-dimensional perception, human civilization grew through two dimensional representations. To grow a civilization, you need to have ideas (which were no longer a problem, since humans had evolved such big brains). But you also needed a way to share them. Complex spoken language & syntax were also byproducts of having evolved such a large brain, and allowed groups of humans to communicate complex plans and ambitions. However, they were limited to the other humans within earshot. It was ultimately the development of written language (around 5,000 years ago) that birthed civilization, because it allowed humans to communicate across vast distances, and over generations.

To accomplish such great feats, we needed to take all of our brilliant ideas (conceived in three or four dimensions) and ‘flatten’ them down to two dimensions, so that they might be disseminated, recorded, and reproduced.

This ‘flattening’ is integral to how ideas are spread. It is no accident that mankind never developed a three-dimensional form of writing. It is difficult to even conceive of such a thing. We leveraged two-dimensional writing, even on three-dimensional objects because while three-dimensional representations might have conveyed permanence, two-dimensional representations enabled copying, and portability, and therefore a much wider scope of communication. It would have done me no good to fashion my laws into the façade of my church, if there were no means for those laws to be copied and carried over yonder.

Flattening Architectural Ideas

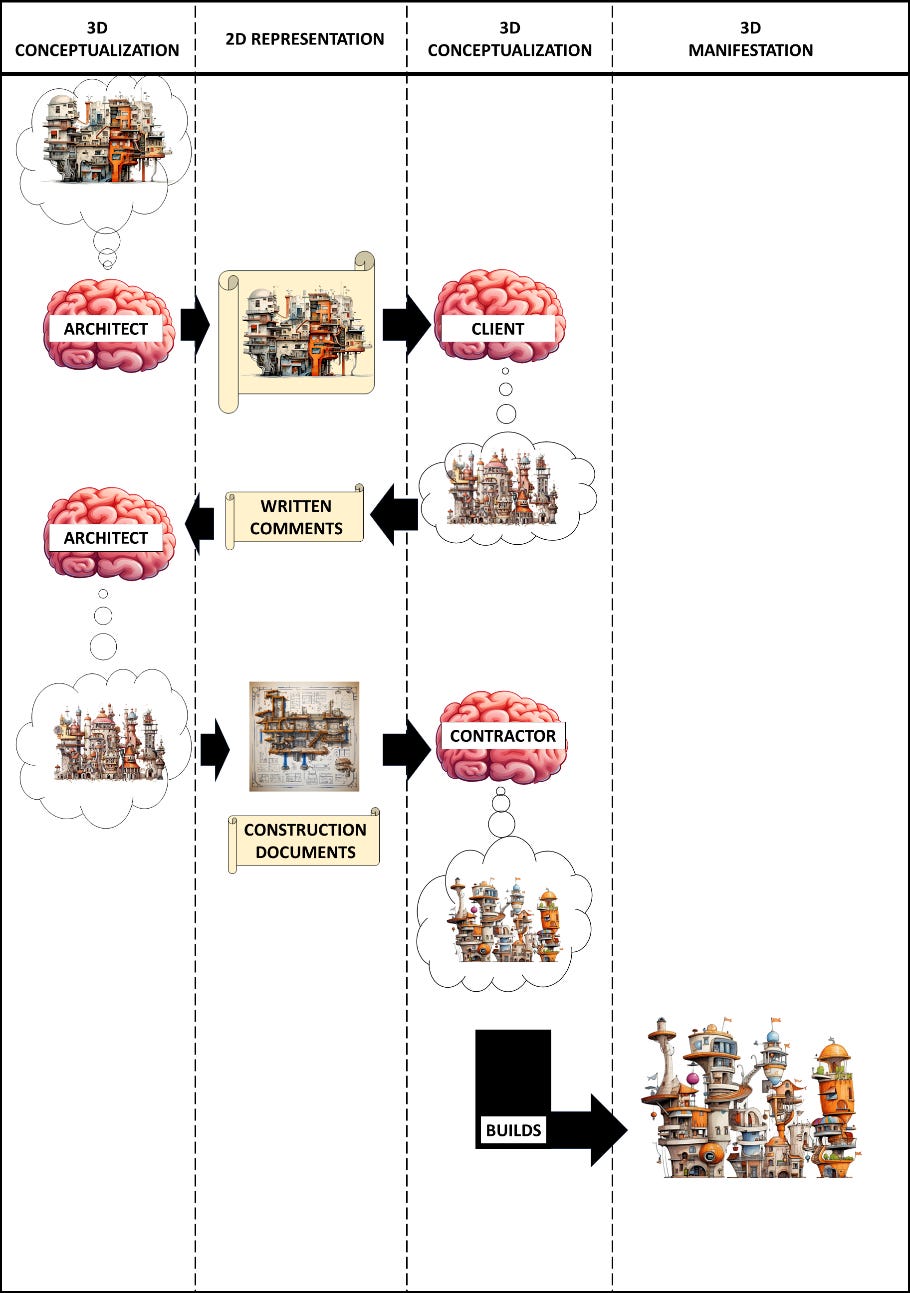

In the communication of ideas, the communication of architectural ideas presented special challenges. Architectural works usually involved lots of people and resources, and the eventual assembly of any project required intense precision. The ancient architect, therefore, was required to imagine things in precise, three-dimensional detail, and then flatten those imaginings into equally precise two-dimensional drawings, so that the eventual re-translation into built form would be successful.

In a way, that has always been architects’ magic superpower: being able to translate between a four-dimensional world – either real or imagined - and flattened, derivative three-dimensional and two-dimensional representations of each. Is it because clients and contractors can’t think in 3D? No, of course not. Everyone thinks in 3D. That’s how the human brain works. But in order to communicate a 3D idea to another human, it must first be flattened to a two-dimensional representation, so that the other party can observe the representation, and then construct their own mental 3D model of the idea.

To execute an architectural project requires doing this many, many times (nearly constantly), and devising representations that are tailored in such a way that the receiver of the representation constructs their own 3D model accurately. If the architect has done her job right, then everyone should have the same mental, 3D idea of what the building is going to be like. However, the representations that get them there may be quite different. A plumbing riser diagram and a glossy rendering look quite different, but they represent the same process: they are the flattening of a three-dimensional idea (for a building, or parts of it) into two-dimensional representations so that the receiver (the plumbing subcontractor, and the client, in this case) can construct coherent, mutually aligned 3D mental models of what the building is eventually going to be.

Like all means of human communication over the last 5,000 years, this had to happen in two dimensions, because the media that we devised to copy, carry, and share ideas was always two-dimensional. Even if you could build a three-dimensional model of a plumbing stack, why would you? And what would you do with it? You could not easily copy it, or mail it, or fax it. It might convey a more accurate representation of your intent, but it would fail in its primary mission of communication.

This History of Ideas: from 2D to 1D

The digital age represents an interesting step in our human history of communicating ideas. Until the dawn of computers, just about everything had to be written down in order to be copied, mailed, faxed, etc. Perhaps for that reason, the ‘flattening’ done by computers bears the legacy of our printed past. Most of how computers are designed and set up is driven by the expectation that their contents will eventually need to be expressed in some physical, two-dimensional form (e.g. printed).

Most architects these days already work in ‘3D’ in the sense that they design with three dimensional models, held in a digital space. But, like almost every digital thing, it is done with an idea that that thing must eventually be expressed in the two-dimensional world (in this case, in the form of a drawing).

Computers also add another dimension to the impressive magic wrought by architects. To communicate a three-dimensional idea through a computer, it must be reduced to bits. This could also be understood as a form of flattening. In a sense, we flatten all of our ideas down to one dimension. A bit is either on, or off. Either a 1 or a zero. But by reducing a complex idea for a three-dimensional building into a series of ones and zeros, it can be sent through fiber optic cables, where it can be reassembled elsewhere into two-dimensional images that someone else can then interpret. Those two-dimensional images can then be interpreted and a three-dimensional building can be erected.

The contemporary architect, therefore, must shepherd an idea further and farther: from the four-dimensional idea, to a three-dimensional model, viewed on a two-dimensional screen, which is then reduced to one-dimensional bits, transmitted, and reproduced as a two-dimensional drawing, which can then direct the erection of a three-dimensional building. Phew!

The Future of Ideas: from 4D, to 1D, and back to 4D

While this special ability is remarkable (seriously, not many other professions have the spatial ability to do this sort of thing), is it fundamentally necessary? All this ‘flattening’ really only serves one purpose: communication. We flatten ideas into two-dimensional representations so that they can be communicated to other humans. We flatten those two-dimensional representations into one-dimensional representations (bits) so that they can be communicated to, and by, computers.

But what if all that communication could be done without the intermediate steps?

Imagine building a primitive hut with a few close friends. You wouldn’t devise complex drawings, or email them to your friends. You’d just say ‘put this twig here’ and ‘cover that thing with mud.’ You and your friends would be working in the actual, four-dimensional world, and your communication in that world is easily done, having evolved over millions of years.

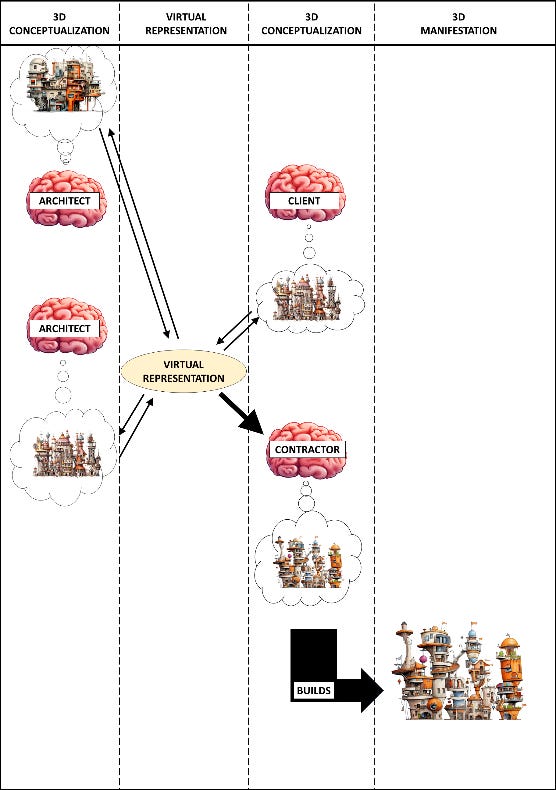

Spatial computing creates a facsimile of exactly that sort of ‘primitive’ designing and building.

If we are designing the structural system for a building, and are working, virtually, inside of a BIM-type model, there would be no need to enter commands in written text on a keyboard or adjust its position with a mouse that moves in a two-dimensional plane. We could reach out, grab it, and stretch it with our hands. Moreover, there wouldn't be any need to adjust notation to "W6x34." We would just stretch it, with our hands, into a W6x34. The contractor wouldn’t need an email to tell him that it had been changed. You wouldn’t need to sketch out the change in that particular pictographic language which architects and contractors use to communicate with one another. The Contractor can just look at it. The change is self-evident.

All of this requires a digital platform. Therefore, there is still a flattening – but it can go from a four-dimensional idea to one-dimensional bits, and back out again, without the need for intermediaries in two or three dimensions.

If we carry it to its logical extreme, spatial computing may represent a full circle, whereby computers return us to the four-dimensional world that we originally evolved to inhabit. Granted, we are all very used to looking at drawings. But that’s not what our brains evolved to do. Our brains inherently ideate in four dimensions – it is only our need to communicate those ideas that gives rise to two-dimensional representation.

Spatial computing gives us the opportunity to collapse ideation and representation into a single process.

Spatial Computing: Product Flop or Revolution?

I will reiterate that I am not an Apple fanboy. But you have to give props where props are due. Apple's legacy, in many ways, has not been the release of products, per se. But rather, the release of new ways of doing things.

Before the iPod, we listened to music via LPs, then 8 tracks, then cassettes, then CDs. Every one of these products came with another product - a device on which one had to play the media. While everyone was trying to figure out what the next combination of media/media player was going to be, Apple advanced a different idea: what if it was just one device? What if you could carry the media and the player together? The 'media' is, in a sense, still media - it's a collection of bits and bytes (and you still have to pay for it). But Apple did away with the idea that there should be complimentary products needed for your music collection. The revolution wasn’t just portability - we already had walkmans and discmans. The iPod was an entirely new way of doing a thing (in this case, listening to music).

The iPhone was a similar stratagem. At the time of the iPhone's release, Blackberry controlled 70% of the domestic mobile device market. It was an indispensable gadget for any white-collar worker, because it allowed one to send and receive emails on the go. Blackberry's response to the iPhone's debut was famously tepid and shortsighted, because they didn't understand what the iPhone was. The Blackberry was a device designed to allow you to send & receive emails on the go – it was designed to do a thing. The iPhone wasn't particularly designed to do anything. It was functionally a computer, stuffed into a phone casing. The idea was to create a mobile device that would allow one to do anything that one could do with a computer. The most important thing that one can do with a computer is to program it, because that gives rise to all the other things that a computer can do. Cramming that kind of hardware into something the size of a phone was a feat unto itself. But the real revolution was in the programming. How do you make a device programmable, when most of the world doesn’t know how to code? Answer: the App Store. A means by which the global community of developers could collaboratively design all the things that people wanted their phone-computers to do. The market interaction between millions of citizen-developers, and billions of customers, meant that the iPhone was effectively programmable by anyone – it all depended on what apps you installed on your personal device.

Apple seems poised to do something similar with the Vision Pro. My suspicion is that they aren’t introducing a product as much as they are introducing the world to a new way of doing things.

What kinds of things? Everything we do with a computer – which is pretty much everything.

Ultimately, the Apple Vision Pro (or its successors) will change how we compute (and therefore everything else) because it enables means of creation more in sync with how our brains evolved to work.

This might momentarily rob architects of their cherished superpower. What good is being able to do all that 4D-3D-2D-1D translation in a world where ideas only move from 4D to 1D and back? But I think it could also be a boon for architects because that’s how architects think too. We imagine whole new worlds in 4D, and yet most of our time is consumed in translating those ideas into lower dimensions so that others might share in them. What if we didn’t have to? What if the power, creativity and inspiration embodied in our ideas were instantly discernable to all? What might we create then?