The Basic Lesson

“Always fix the first problem first. Any given day will present you with 100 problems. Find the 4 or 5 problems that are causing all the other problems. Find the one problem that’s causing those 4 or 5 problems and deal with that first. Prioritize it with all of your time and attention. Working on downstream problems is fundamentally a waste of time and energy. You have to have the courage to forcefully ignore everything except the first problem.”

Air Travel, as a Disaster

We’ve all been there: those moments in your life when you feel completely overwhelmed and you don’t know which end is up. When you feel like you just suffer crisis after crisis and life won’t give you a pause to catch your breath. For a disaster responder, that’s pretty much every day. The first day in a new disaster zone is usually the worst. The suffering is the greatest, and the resources are at their lowest.

While there are extraordinary experiences in a disaster response, outside the realm of most people’s everyday experience (e.g. flying around in helicopters, attending mass-burials), in an actual disaster zone, you’ll find that many of the same everyday activities you enjoy/endure in your own life also occur. People still make coffee, or buy airline tickets, or go to meetings, for instance.

In a disaster zone, the easy things are hard, and the hard things are often impossible.

Disasters, by their nature and definition, turn simple tasks into little ‘disasters’ of their own. How do you make coffee if there’s no water? Or the water is contaminated? Or the power is out? You often find that what would be a 5 minute task in any ‘normal’ situation might consume a whole working day. And when it does, you can be sure that the stuff you didn’t do today will be causing some other disaster tomorrow. In disaster zones, you often have to figure out the bare necessities before you end up getting to the actual reconstruction work. There’s also a strong temptation to work on the most urgent problem, which is very different than the first problem. Being able to isolate the ‘first’ problem in any given situation isn’t always the most immediately gratifying path. But it is the most ultimately gratifying path. And it provides the key to solving complex, opaque problems that dog our modern existence.

Hell, Up in the Air

I had a chance to think about this recently when I was flying on Volaris Airlines to Mexico. For those that don’t know, Volaris is the second cheapest Mexican airline, somewhere in line with Spirit Airlines. Like anyone else who travels anywhere at this point, I got to think about the unbelievable dysfunction of the airline industry, and how it was possible to make air travel so f***ing miserable for everyone.

I leapt to two obvious culprits: 9/11 and the Corona virus pandemic. 9/11, obviously, made the process of getting into the plane much more onerous. And the supply chain problems flowing out of the Corona virus pandemic complicated business for the airlines as much as anyone (or so we’re told).But that didn’t quite cover it for me. In disaster work, you get used to looking at non-obvious explanations. You do this because disasters inherently avoid the obvious; if the hazard were that obvious, people would prepare for it, and you wouldn’t have a disaster to begin with. No U.S. city has ever been taken over by packs of rabid, feral dogs.

We all understand the inherent danger that a pack of rabid, feral dogs presents.

And we built systems to ensure that that didn’t happen.Every disaster always has a complex story behind it, often stretching back centuries. In my research, I’ve traced the origins of the Haiti Earthquake back at least 200 years, and the origins of Hurricane Katrina by about 100.

You can pinpoint exact events, people and policy decisions that effectively laid the groundwork for the disaster that arrived long after they passed. This isn’t in order to vilify them, necessarily, but in order to better understand the phenomena itself, and perhaps avoid calamity in the future through closer inspection of our actions in the present.

When undertaking a “Fix the First Problem First” analysis, I usually begin with the problems closest to me, and easiest to understand. In this case, I began with “my legs hurt” and worked backward from there:

My legs hurt because this seat is cramped

this seat is cramped it was designed to be barely tolerable, and maximize the number of seats in the aircraft

it was designed to be barely tolerable, and maximize the number of seats in the aircraft and therefore maximize profit

But . . . You usually don’t maximize profit by torturing your customers

If torturing your customers is profitable, then that means a lack of alternatives, because who would submit to this if there were an alternative?

I submit to this because there was no alternative

There was no alternative because driving to Mexico would take 2.5 days

Also, there was no alternative because this was the most ticket I could afford

this was the most ticket I could afford because flying is outrageously expensive

flying is outrageously expensive because their costs are high, and they pass it to the consumer

But . . . if their costs were high, and they passed it to the consumer, they would be profitable, which they’re famously not

A Genuine Mystery

It’s a mystery: how can a business provide a terrible service, charge outlandish prices, lose money, and still be in business?

Conclusion: They must be making it somewhere else

In my cramped little seat, I wanted to do some research. In a series of contortions, I managed to extract my wallet from my back pocket, and my laptop from my carryon, and purchased the outrageously overpriced wifi so I could do some digging.

The first thing I confirmed was something we probably all already know: the airlines increasingly do less and charge more for it. As of August 2022, the airline industry in the United States was flying 25% less than pre-pandemic levels in 2019, and charging 45% more for flights, which meant that the airlines should be outrageously profitable, which they’re not. So, I adjusted my thinking cap.

I remembered from business school that historically, airlines aren’t terribly profitable businesses. Prior to the Covid pandemic, the airlines were averaging about 20-30 billion dollars in profit on 700-800 billion in revenue. Depending on which year you’re talking about, you might be looking at 2-3% profit margin. And that’s only possible because some airlines do a lot better than that. A handful of airlines might post profit margins of 5-10%, which offsets the fact that a lot of airlines are in the red.

As my First Problem investigation was picking up steam, the flight attendants began their spiel, including the now-ubiquitous advertisement for a new credit card.

I considered how gauche it was to overcharge people, cram them in a confined metal tube, and then try and sell them more debt.

But, the spiel helped me consider the problem in a new way.

I reflected on Rule 8: Just Because it’s a Disaster for You, Doesn’t Mean it Ain’t Workin’ for Somebody Else. Yes, air travel is a disaster for passengers. It doesn’t even seem that great for the airlines themselves. But if it were a disaster for everyone it would get fixed. Chances were, it was making a lot of money for someone, somewhere.

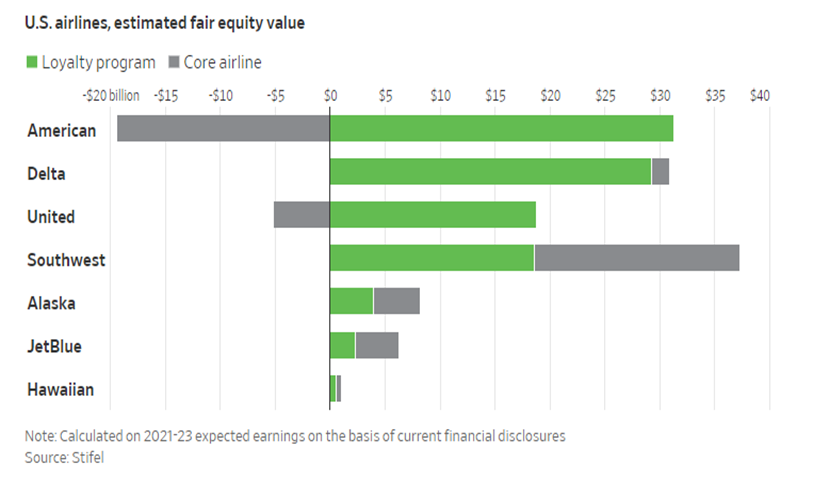

The Covid pandemic response had a slurry of unintended consequences; one of them was a level of unprecedented transparency from the airline industry. The airlines were forced to cough up some of their data as they appealed to the Federal Government for support during the pandemic. In those disclosures, it was revealed that for most airlines, the frequent flyer program is at least as profitable as the airline itself. In some cases, the valuation of the frequent flyer programs was many times more than the value of the entire airline business! (Source: WSJ)

We hadn’t seen this data before because airlines (like every other company) aren’t necessarily required to publicly disclose which aspects of their business are profitable and which aren’t. Especially if they can make the case that multiple business lines intersect and overlap. If you run a McDonald’s, you can’t necessarily evaluate the profitability of burgers and fries separately. Because sometimes people come in for a burger and end up getting fries as well. Or the other way around.

Such was the conventional thinking with frequent flyer programs. They were ‘marketing’ designed to encourage customer loyalty. They weren’t necessarily separable from the core business of flying planes and taking passengers from here to there. Good service made marketing easier. And good marketing allowed you to charge higher prices.

It brought me to two main questions, which I noodled on while trying to decide whether to order an over-priced snack pack.

1. How could a marketing program make money? Marketing was the money you spent so that people would buy your products. It usually didn’t make money unto itself.

2. How could a marketing program make that much money? In the case of American and United, the frequent flyer program was worth billions while the airline itself had a negative valuation – it was worth negative money. That’s insane. That means any one of us could become owner of American Airlines, and they would have to pay us to take it.

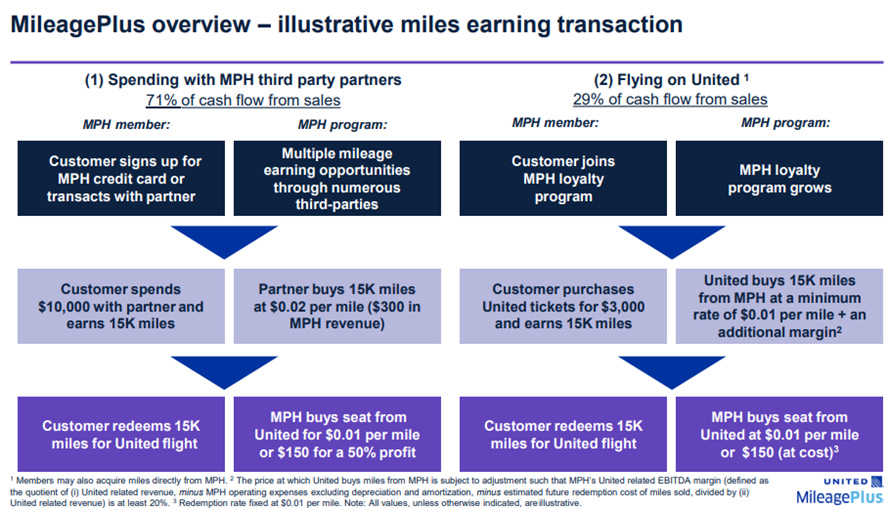

As usual, it was in the fine print. In this case, the actual investor presentations that United makes publicly available to investors. What makes all this work is the treatment of frequent flyer miles as a kind of shadow currency. They have value inasmuch as they can be exchanged for cash. But only internally.

An airline, United in this case, sets up a ‘bank’ to regulate that currency. They remain in charge of determining the rates at which miles get exchanged for dollars, seats, etc.

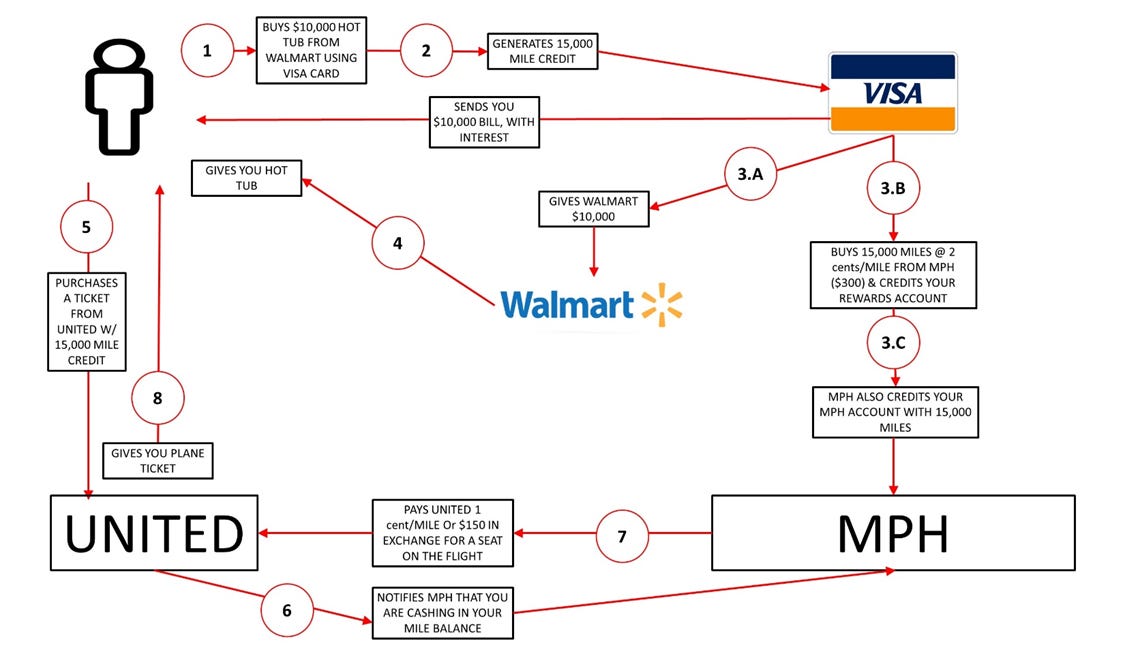

If you get a United card and buy a hot tub for $10,000 from Walmart using your Visa Frequent Flyer card, VISA pays Walmart for the hot tub, so that you can take it home, and then turns around and buys the equivalent number of miles from MPH (the bank) at a rate set by MPH (in this example, 15,000 miles @ 2 cents/mile. or $300). Those miles are credited to your frequent flyer account, and MPH keeps the cash that it just received from VISA. Once you decide to redeem your miles, you indicate to United that you’re going to be using miles, and MPH buys a seat from United at a rate that United itself determines (in this case 1 cent/mile) using the cash that it received from Visa, holding back a certain % for its own profit. In this case, it is redeeming your 15,000 miles for $150, which is the price that it pays United for a seat. It pockets the remaining $150 it received from VISA, as pure profit!

The miles ‘bank’ is making money hand over fist. For instance, in 2019, American Airlines disclosed that its loyalty program (Aadvantage) generated $5.9 billion in cash with a 53% profit margin.

I took a step back and considered that it’s generally impossible for a business to not try and make money. The C.E.O., and the board, have a fiduciary responsibility to try and maximize return on shareholder equity. So it would actually be illegal for them to provide such a terrible service, unless that terrible service were somehow making more money than providing a good service. And such is the case with air travel and frequent flyer programs. The shittier they make the experience of flying, the more tempting it becomes to buy in to one of those frequent flyer programs. You could get an upgrade! You could move to the front of the archaic, byzantine boarding process! Free snacks! By making flying more and more miserable, they funnel people into rewards programs, where their true profitability lies.

What Can We Do About It?

The fix seems simple: break up the ‘banks’ the live within our airlines. MPH is much worse than an actual bank, because they get to determine the rate at which miles are exchanged for cash. If you went into a bank to deposit $10,000, and they issued you 10 Willy Wonka golden Tickets in exchange, it wouldn’t necessarily be the end of the world. Those tickets might be very valuable to someone, and you might actually get to exchange them for more than $10,000, making a profit. But if the bank told you, on your way out, that the Golden Tickets can only be redeemed at the bank, it might give you a little cause for concern. If they subsequently told you that they could, at any moment, decide from one day to the next what the exchange rate between dollars and Golden Tickets was going to be, you would rightfully conclude that it was a complete scam. You would turn around and try and exchange your Golden Tickets and get your $10,000 back. You would fail, because the bank has already adjusted the exchange rate, and your ten Golden Tickets are now worth only $8,000. Sucks to be you.

We could pass legislation to inhibit all this. Legally separating the in-house airline banks from their airline parent corporations would force each entity to consider its own individual profitability. Airlines would have to improve services, in order to get more customers. And the Frequent Flyer Milebanks would have to actually deliver some service of value, rather than just depending on the shittiness of airline travel to create an artificial demand for their product.

Final Thoughts

The Rules of Disaster can sometimes give you insights into disasters at large, and sometimes into disasters in your own life, and sometimes both. Sometimes, though, it feels like neither. Sitting in my cramped window seat, already aching from the forced contortion, I felt a mixed sense of relief. It eased my mind to solve the ‘mystery’ of why airlines suck. But there wasn’t anything I could do about it from there. I couldn’t even get up to pee, as my partner had already fallen asleep.

Rule 1: Fix the First Problem First is always first in my mind. When I’m training disaster responders, or find myself in a disaster situation, I always start there. I advise responders to ignore everything except the first problem, and that working on anything else is a waste of time & energy. I could, for instance, solve the problem of “My legs hurt” by getting up and walking around. But my legs will just hurt again later in the flight. Or on the next flight. Everyone’s legs are going to hurt until we look at, and solve, the first problem: a commingling of airline business lines that makes it more profitable to provide worse service.

Strangely, that didn’t feel fatalistic to me. But admittedly, it didn’t do anything for my achy legs. Whether you’re trying to solve some pervasive social problem, or a personal disaster in your own life, the technique is the same. I hope you get a chance to try it out, and hope it helps. Please be in touch if you have results you want to share, and don’t forget to subscribe.