How A.I. Will Change How Architects Design in 2025

Design in ‘25: The Near Future of Architecture & A.I., Pt. 2

In This Post:

Unpacking 2024 . . .

In 2025 . . .

‘The Sims’ Emerge as a Hot New Design Tool

Digital Twins Seek, and Eventually Find, Profitability

Unpacking 2024 . . .

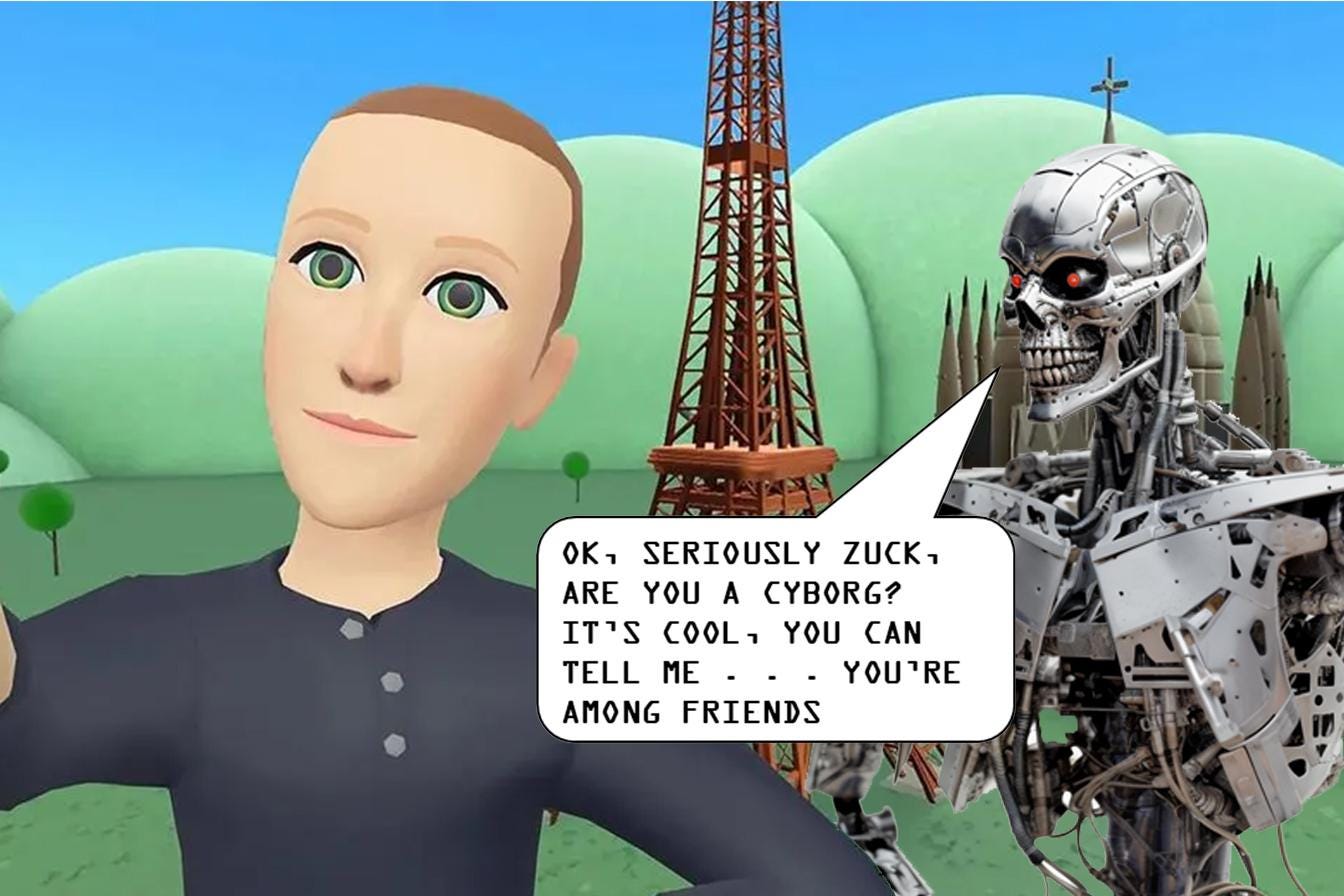

In 2024, I predicted that the Metaverse would transition from a novel toy to a serious design tool and, along with AR/VR, become the emergent medium in which architects design. So far, the metaverse has been pretty disappointing. We all thought we'd be doing kung-fu in the Matrix by now, and what we got was Mark Zuckerberg playing Pong on his glasses. The full emergence of the metaverse is a complex problem, requiring software, hardware, and infrastructural improvements. Regardless, the pieces of the metaverse continue to come together and their individual development is accelerating. That should suggest the increasing urgency of designing the metaverse before a bunch of computer nerds do it, an argument I explored in 2023's "MYTH: 'Architects Won't Have a Role in an A.I. Future."

Over the course of 2024, a couple of new 'metaversal' developments strengthened my conviction:

In 2025 . . .

‘The Sims’ Emerge as a Hot New Design Tool

The metaverse, without AI, is an interesting conceptual design problem - how do you organize it? Are there roads? How high are the ceilings? The metaverse, inhabited by A.I.’s, becomes a formidable design tool.

Common perceptions of the metaverse suggest that it's some kind of digital ghost town. I sit on my couch, and put on my headset, in order to connect with you, who is also on your couch, wearing your headset. The technology allows us to rendezvous at the metaversal Starbucks, where the barista, who is also sitting on their couch, can don their headset and whip up our metaversal lattes.

This is unlikely to occur. Why would you need a human barista to jack into the matrix and make you a fake latte, when an artificial person would be (in the context of the metaverse) completely indistinguishable?

The metaverse will be bustling with artificial people, doing all sorts of jobs. They have inherent advantages: they can work 24 hours a day, and don't require a couch or headset to participate.

For a designer, these artificial people represent the perfect guinea pigs to weave into the design process, a concept I explored in my post 'An Intuition on Simulation' A designer can design a building virtually, populate it with customized, artificial tenants, and then speed up time ten thousand fold to see how people will eventually use the building.

We do not have to wait until the metaverse is fully baked. This technology is available, now. Google recently released a generative physics engine called “The Genesis Project” that’s free, open source, and considerably faster than its predecessors like Isaac Gym. (BTW, if you follow that link, you’ll see that the Isaac Gym, revolutionary in 2022, has already been decommissioned as obsolete – just, wow).

Several firms I know of have already developed AR/VR programs as a means of displaying work - they find it to be a useful tool to help clients understand a design (FUN FACT: We recently saw the first example of a judge donning a VR headset to experience a crime firsthand, from the bench, during trial).

As the digital verse expands in quality, and ubiquity, we can expect that the metaverse will increasingly be a place for doing the design, not just showing it off. Accordingly, we should expect AR/VR technologies to gain greater purchase in architecture schools, as well. There’s an obvious argument that we should be training young architects for the tools they’ll need in the workplace. But there’s also a more nascent argument: AR/VR makes learning better. A recent survey by PwC showed VR Learners learned four times faster than learners in a traditional classroom.

Digital Twins Seek, and Eventually Find, Profitability

Part and parcel with the metaverse, we should expect that digital twins become a more ordinary part of practice, although not at the pace that some of us would hope. Digital twins represent a simulated reality that the owner, designer, and builder can share, both before, during, and after construction. They're a 'sandbox' for doing anything we want to do, without the ramifications of doing it in the real world. One would think that that has easily understood benefits for all three parties, and aligns with the goals of each. But if it were, creating a digital twin for every project would just be a given.

The relationship between owner, designer, and builder has cultural, economic and legal dimensions, which all evolve more slowly than technology. For that reason, it will continue to be a struggle to find ways to monetize digital twins, and to convince owners of their value. For an owner to invest in a digital twin, they must be open to the idea that an architect can have an ongoing role in a building's life. As we all know, once the ribbon cutting is over, architects and contractors often only get a call once something has gone wrong.

To truly extract value from a digital twin, the relationship between owner, designer and contractor must evolve into something less transactional. The three should understand each other as a durable team, charged with ongoing stewardship of the building and the value that it represents. Of course, we could do that now, without any AI, metaverses or digital twins. But we don't - and that's a historical discussion outside the scope of this piece.

Regardless, digital twins may be the technology that finally overcomes that professional anachronism. Particularly progressive clients and their progressive designers will lead the way, as they tend to do. There will be plenty of stumbling blocks; there will certainly be clients who end up resentful when the value they create out of their digital twin doesn't rise to the level that they expected when they paid for it, and doesn't do all the things their architect said it would do.

But the technology only moves in one direction. As does time. As time goes on, the success stories will pile up as well. Three years after a building's completion, a client will use their digital twin to resolve some problem, or make some repair, or alteration, and they will realize that the money they paid to build the digital twin is paying off. Thereafter, they'll insist that the creation of a digital twin be included as a part of any contract. I imagine that As-Builts became an industry norm in similar fashion.

The cost of making digital twins should fall, as we get better algorithms for the procedural generation of buildings, and whole cities. (See Section ‘Parametricism Evolves Into ‘World Building’ in How A.I. Will Change the Way We Feel About ‘Design’ in 2025)

The cost of not making a digital twin should rise out of pure economics: most technologies scale their utility with the number of users. Having a phone isn’t useful if no one else has a phone. But for every new user of the phone, the utility of owning one scales exponentially. At some point, the cost of not having a phone is a net negative.

If you enjoyed that, be sure to check out Part 3 of this series: 'How A.I. Will Change How We Build in 2025’ and subscribe below for all future updates.