Fast-Learning for Architecture Firms

The Five Optimizations for an AI-First Architecture Firm (1 of 5)

In this Post:

Understanding the Learning Zone

Your Office Idiot

Three Key Maxims for a Fast-Learning Firm

(For an intro, check out ‘The ‘AI First’ Architecture Firm’)

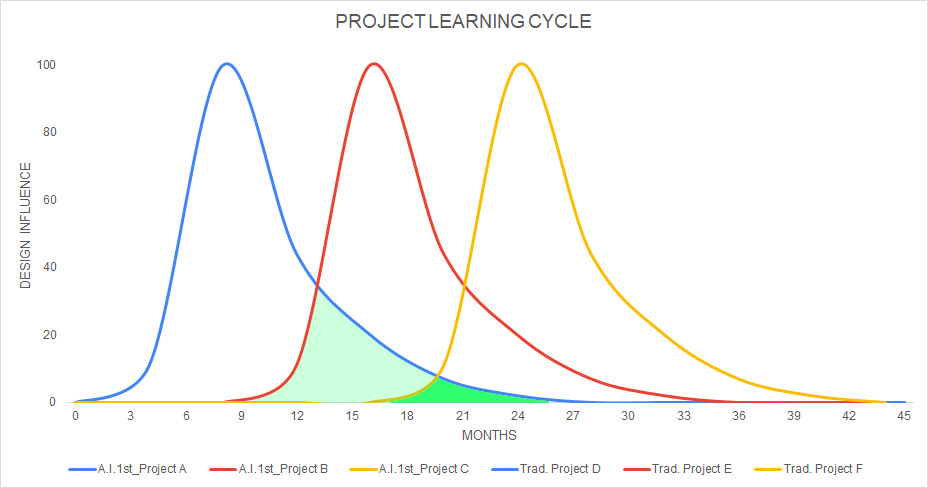

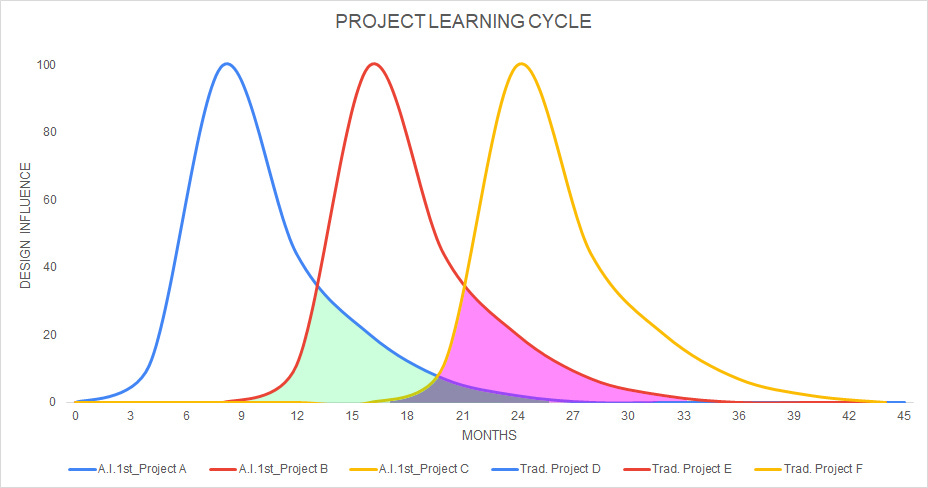

Every firm must immediately develop a fast-learning protocol. I’m guessing half my readers just through their hands up and said ‘we already learn fast!’ No, faster than that. I learned how to be an architect by moving through project cycles - like any other architect. There’s a learning that happens when something you drew in 2022 is erected onsite in 2023 and you realize ‘Oh, that’s how that works.’ That takes years, decades even. Architects learn from each other, and projects learn from other projects. Most well-run firms have some kind of ‘lessons-learned’ protocol where they’re able to do a post-hoc analysis of how the project went and hopefully share those lessons outward with the rest of the firm, and onto future projects. We call this ‘The Learning Zone.’ (in green).

Understanding the Learning Zone

It’s when Project D has gone through enough of its own life cycle to be able to communicate lessons to the forthcoming Project E. Those working on Project E can benefit from all the mistakes that were made on Project D, hopefully. As projects continue, the cycle continues and reinforces firm learning.

When we begin Project F, it is able to learn more complete lessons from Project D, because Project D is farther along in its life cycle (dark green).

Project F also benefits from ‘double learning’ - it assimilates lessons from both Project D and Project E:

This is how architects (and firms) build competence. That should be familiar to any architect. But what happens when the project cycles are extremely compressed, as they will be under NLGAI?

The time we might have to learn from our mistakes is compressed. The period of reflection feels almost non-existent. But don’t despair!

We have to make a critical distinction between between people who learn fast, and organizations that do. Having people that learn fast is great. But its not the same thing as having organizations that learn fast. The latter is more important. Ask yourself these questions:

How are successes recorded? Are they shared out instantly? Are they embedded in a resource where people can easily find them?

How are errors detected and integrated into lessons learned?

For both errors and successes - is the knowledge just available? Or is it institutionalized?

Your Office Idiot

I’ll envision a cartoonish example: suppose you have an employee in your office that isn’t too bright, and ends up printing out a contract with disappearing ink. How did he find a printer cartridge with disappearing ink? I don’t know - it’s a cartoonish example. But he did it, and now you have no evidence of the contract that was signed between you and the client. This could present all sorts of problems. One approach to preventing a reoccurrence would be to reprimand the employee. Another approach would be to email or Slack the entire firm and remind them not to print contracts in disappearing ink. Another approach would be to buy a year’s supply of regular ink and store it in the office, so that no one is ever tempted to fill the printer with invisible ink. A fourth (and better) solution would be to switch over to digital contracts. That’s not a cure-all. The office idiot may find a way to screw that up, too. But the learning from the error has been institutionalized in the sense that no one has the option of using invisible ink anymore, because no one is using any ink. And that’s something you can do today, before anyone else makes the same mistake.

The specific steps to implement a fast-learning protocol at any firm will vary widely, depending on the firm. But every firm has to understand this reality: doing projects 100x faster means that you can make mistakes 100x faster. There has to be a specific plan in place to detect, memorialize, communicate (and ideally, institutionalize) both errors and successes, and it should rely on a minimum of human intervention. Institutionalizing successes and errors is critical because it allows the firm to learn faster than the people in it. If it’s the case that you have multiple employees inclined to use disappearing ink, first of all, review your hiring policy, because that is messed up. Secondly, it resolves the potential error faster than it would take to have everyone learn the lesson.

Can A.I. help with institutionalization? Almost certainly, but it would depend on the specifics of the firm. If a firm has had a solid policy of memorializing projects and lessons learned, could a machine review all those archived reports and review current projects for possible similar errors? Yes, it could. Could you trigger this to happen automatically when a project reaches 90% completion? Absolutely. Could you program a machine to review existing projects on a nightly basis, after everyone goes home? Yup. Could a machine be programmed with the successes of past projects and offer contextual suggestions to designers, as they’re designing. Also, yes.

A Fast-Learning system doesn’t necessarily have to depend on A.I. But it probably should. Either way, it should adhere to the following key maxims:

Three Key Maxims for a Fast-Learning Firm

Rapid, frictionless recording of both errors and successes. The days of waiting until project completion to record wins and losses are over. Successes must be recorded in real time, so they can be passed on to the next project. Errors must be recorded in real time so that they don’t pass to the next project. The recording system should not depend on anyone’s initiative to sit down and record wins and losses at the end of the day. No one has time for that. Take humans out of the equation, as much as you can.

The ability to easily and contextually surface those lessons. People don’t usually know that they’re making errors as they’re making errors, so expecting anyone to go sifting through an archive and find the errors they don’t know they’re making seems like a flawed strategy. The lessons must be institutionalized (e.g. switching to digital contracts) or they must automatically surface where they’re needed.

Democratically organized, nonhierarchical system. Its not always the top managers that find the mistakes. The more a firm commits to ‘learning in public,’ the faster the firm will learn. The system should be organized such that anyone can record errors, develop solutions, and otherwise participate in the fast-learning system.

You can check out the next installment “Micro-Scale Innovation” here, and subscribe to get notified of further posts.