Addressing Future Talent Shortages in Architecture

How A.I. Presents a Pipeline Risk for an Incoming Generation of Architects

In This Post:

Why I Don’t Churn my Own Butter

Charting the Growth of A.I.

Four Career Trajectories for Architects

Most architects I know are struggling with a predictable, but specific talent shortage: because of the losses of the Great Recession, they’re now seeing a dearth of mid/senior architects, relative to more senior architects and recent grads. By some accounts, roughly 1/3rd of all U.S. architects left the profession in the wake of the Great Recession. Many of those were at the time recent grads or young professionals, and presumably judged that they were young enough to still make a career pivot. Similarly, the Great Recession caused a dip in architectural school enrollment, as students sought out more recession-proof occupations.

A well-functioning firm depends on architects of all experience levels and skill sets. And there are ancient traditions of mentorship through which knowledge is handed down, from architect to architect, generation to generation. Civilization owes itself to such traditions. From what I can tell, most firms are doing okay, though. The fact that that mid-career architect population is a little smaller is observable at a macro-scale, and poignant for any senior architect who’s trying to hire a mid-career architect and can’t find one. But the long tradition of generational knowledge transfer faces a much more formidable challenge in the near future.

Why I Don’t Churn my own Butter

When I was in college (mid 90’s), I remember my father cautioning me against choosing this major or that one because he feared that it would be displaced by ‘the internet.’ This was an older time, and he was an older man, and it wasn’t uncommon then to believe that ‘the internet’ or ‘computers’ were going to end up sending us all out to pasture.

I recently spoke with a friend who’s a parent of teenage children, getting ready for college, and she echoed my father’s concerns from a generation earlier . . . that her kids would major in something and it would just be displaced by “AI.” I shared my own story from back in the day, and we had a shared laugh at my father’s naivete – the Internet came, became a part of our lives, and employment is higher than ever.

However, I got to thinking about that technological revolution, and others before it, not in terms of the jobs that were lost, but in terms of all the capabilities that had been lost throughout time. There’s so many things that we no longer know how to do. Like churning butter.

500 years ago, I might have been called upon to churn my own butter. I don’t do that, and no one else does it for me. It’s done by machines, on industrial farms, and I buy my butter at the grocery store like everyone else. I don’t even know how to churn butter. That doesn’t worry particularly worry me - there are lots of things I don’t know how to do. But I found myself wondering whether anyone else knows how to churn butter. I’m pretty sure none of my friends and family do. Is there a craft farm somewhere where they still churn butter by hand? Probably. It’s probably done for touristic purposes, and the sort of place where children go on field trips.

I got to thinking about what the architectural equivalent of ‘butter churning’ might be. There’s a host of skills that were once part of an architect’s central job description, that seem to have largely fallen out of our realm of competency. A century ago, architects were understood to be master-builders. They were there, in part, to show tradesmen the right way to build things. They needed to know how to assemble things, not just draw them. And they needed to know how to build better than anyone else on site.

I’m a fairly decent carpenter, but I wouldn’t put my framing ability over and above any actual carpenter at this point. Similarly, I had some facility at hand drafting once upon a time, but I know that students now aren’t even taught that particular craft. Does it matter? At a social level, probably not. But it could matter greatly at an individual level, if you went to school and majored in hand drafting, and that were your only skill. Of course, no one goes to technical school and majors in hand drafting anymore, because it would be impossible to leverage that skill into employment. That’s just common sense.

In the article, and on this substack, I scared myself shitless, because many of the technologies that might assemble an “AI Architect” are actually already available. None of my work so far has convinced me that AI could or will replace architects, necessarily. But it’s going to have profound effects on the profession, whether we’re ready for it or not. Among the most serious might be this: the interruption of generational knowledge transfer that has sustained the modern profession of architecture for its entire history. Ten years hence, there may not be anyone to fill the pipeline. They might not be necessary, or they might be more necessary than ever. Either way, there’s a good chance that they just won’t ever show up to the profession.

Charting the Growth of A.I.

The capabilities of AI in architecture are uncertain. Is it capable of creativity? Will clients trust it? Will architects own it? One certainty is that its capabilities will expand, and expand rapidly. It seems logical that the capabilities of AI in architecture will mirror those of AI generally, which will mirror those of computing, generally. All current data suggest that Moore’s Law has been superseded.1 Real computing power will almost certainly continue to grow at an exponential or even a double-exponential rate.2 We can make certain guesses about what kinds of capabilities this growth will encompass:

Technical knowledge.

From my own experiments with GPT 4, I can say that it has extraordinary technical knowledge of all kinds of architectural and construction issues, and when prompted correctly, can write accurate specs for door hardware and cite building codes from all over the planet. That makes a certain amount of intuitive sense. Open AI (the company that made GPT 4) claims that its training model was ‘the Internet.’ If you forced the entirety of the Internet through your brain, you’d know a lot about building codes and door hardware, too. Of course, you already know that, because you’re an architect. My point is, AI may have already assimilated most of the ‘technical’ knowledge for which we were previously gatekeepers. ‘Professional capability’ is usually defined by types and instances of technical knowledge which cannot be gained casually. You can’t ‘know’ how to be an architect by walking past buildings and sizing them up. It requires intensive, deliberate study of a wide range of technical fields. It seems obvious that AI already has knowledge of those fields, and is learning more quickly.

Generative design capabilities.

As I outlined in the article, the chief limitation at this point in using AI to generate whole-building solutions is computing power: the design of a building simply has too many decisions, too many parts, and too many overlapping, possibly contradictory goals to be done efficiently within our current computing power. I also hinted in the article that that particular limitation is fundamentally, and inevitably decreasing. If we believe in The Law of Accelerating Returns, we can conclude that the limits are decreasing at a double-exponential rate - which is really fast! It seems logical that AI’s generative design capabilities will grow at a corresponding rate.

Communication capabilities.

If you want a sense of how much a few months matters to an AI, take a break and ask GPT 4 to do something mundane, like plan a holiday weekend trip to see the in-laws. Then go over to Bard (Google’s equivalent) and do the same thing. The responses from GPT 4 will be almost indistinguishable from human. Bard will be thorough, but it will almost certainly feel like you’re talking to a very eager machine. That’s because GPT 4 has been learning from 100 million trainers for the last six months. In every conversation, it’s learned to give better, more natural responses. By interacting with 100 million actual humans for the last six months, its started to get pretty good at it, and will continue to get better. All AIs will eventually follow the same course, because they’re all fundamentally built the same way. AI’s ability to speak, understand, and be responsive will also increase exponentially. The more people use it, the better it becomes. The better it becomes, the more people will use it.

For the purposes of our investigation, we’re going to gang all this together under the general category of ‘capabilities.’ Does the sum of these three capabilities make one capable of being an architect? I suppose we’re all going to be debating that for a while. But if Autodesk debuted a robot worker with more-than-human technical knowledge, generative design capabilities, and communication ability, you wouldn’t want to be the only architecture firm without one.

Assumptions:

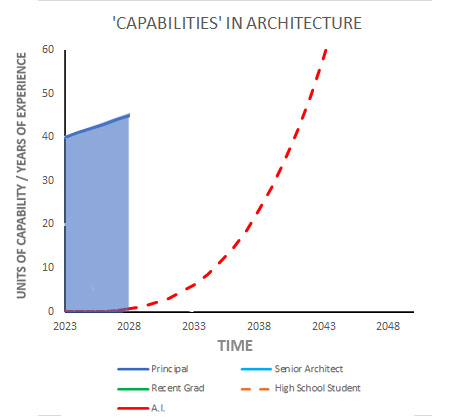

We’re going to make some crude assumptions about ‘capability.’ An architect with 40 years of experience has 40 years of experience, but time can be a crude metric for judging capability. Capability is non-linear, because we learn by doing, and making mistakes. It also raises the question of ‘capable at what?’ Does an architect who spends 40 years in project management at a large corporate firm have the same capabilities as an architect who spends 40 years doing small residential projects as a sole proprietorship? Obviously not - they’re competent at different things. For now, we’ll make some linear proxy between capability and experience. One year of experience = one ‘unit’ of capability. The more experience an architect has, the more capability they have. We’ll be unspecific about what kind of capability that is. But it fits a basic logic: the more time they have at a job, the more competent an architect generally becomes - they learn from experience, from making mistakes, and from other more senior architects. The process is admittedly non-linear in the short-term. But over the long term, it fits.

For now, we’re going to assume that the capabilities of AI are going to be expanding at an exponential rate, for the reasons stated above. For the examples below, I’ve used a basic exponential of y=x^3. Is that correct? I have no idea. It’s a lot slower than a double-exponential rate, but faster than a basic exponential of y=x^2. If you disagree with that assumption, feel free to alter the model or shoot me an email and propose another idea.

Four Career Trajectories for Architects

Now, we’ll consider the trajectories of four architects:

A Principal, with 40 years of experience

A Senior Architect, with 20 years of experience

A Recent Grad, who’s just entered the workforce

A High school student, who dreams of one day being an architect.

Given the fact that AI learns at an exponential rate, and humans learn at a linear rate, we can expect that AI will catch up to human capability, eventually, because all exponential functions catch all linear functions by matter of mathematical necessity.

The Principal Architect

For the Principal Architect, with 40 years of experience, that probably won't matter much. In the near future, the Principal Architect has a significant role to play. AI hallucinates constantly, which amounts to a funny distraction when asking GPT for restaurant recommendations. However, it can be lethal to a firm when contracts are being written and reviewed. So it’s imperative that the Principal Architect be present to be the final point of accountability and authority. AI will continue to be imperfect until it isn’t. And until it is, it’s going to make mistakes (hallucinations) and need to be supervised. The Principal Architect, having amassed a lifetime of capability and wisdom, is the most reliable hedge against the potentially catastrophic mistakes that an AI might make. He or she is both supervisor and teacher.

We don’t know how fast AI will scale in its capabilities, but with the assumptions that we’ve made, our Principal Architect will likely retire while the AI is still on its training wheels. The Principal Architect’s job role may shift a bit, as the whole profession is shifting, but likely they will continue to do much of what a Principal Architect already does (steer the ship, be accountable, and train/mentor whomever is next in line).

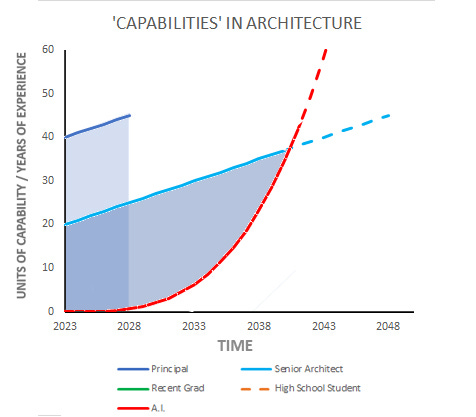

The Senior Architect

The Senior Architect, with 20 years of experience, also still has a role to play, and it’s similar to the Principal Architect’s. He/She will also have a role in training the AI alongside younger staff, and being accountable for its mistakes. In a sense, she is performing the same function that she would otherwise apply to a human subordinate, it’s just that her artificial subordinate learns much faster. Because she is still partially in the trenches, she may also do a lot of the ‘work’ - meaning actually doing drawings and making site visits. But that work is being rapidly replaced by the AI’s capabilities. Towards the end of her career, she’s doing less and less of the actual work, but her role is more and more important, because she represents the only person in the office with sufficient expertise to catch the AI when it has made a mistake.

Around 2040, her capabilities are eclipsed by the AI, which is around the time that futurists predict ‘The Singularity’ where AI becomes smarter than all human beings combined. At that point, there’s probably not much left for her to do at the office. She takes a slightly early retirement, after a distinguished 35 year career.

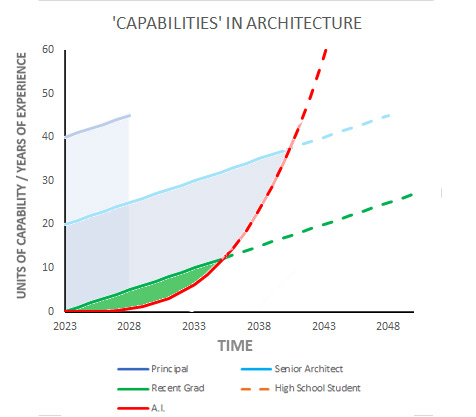

The Recent Grad

The Recent Grad has a much more serious problem:

The AI is charging ahead, learning at an exponential rate. So the Recent Grad never gets to accrue the decades of experience that his antecedents had. Very early in their career, their capability is eclipsed by the AI, so after 10-12 years in this example, they don't have that surplus of knowledge/experience capability which can then be used to train/supervise the AI in the future.

However, their position probably isn’t untenable. Assuming they are young, tech-savvy, and adaptable (as recent grads tend to be), they have 10-12 years to figure this whole thing out (assuming AI is learning at y=x3). They can evolve with the AI, into whatever architecture eventually becomes. Perhaps architects of the future only work on monumental buildings, or have some yet-unimagined role. Whatever it is, the Recent Grad will have to evolve quickly.

The ominous part is that they will lose the opportunity to accrue the kind of human experience that made their antecedents a proper hedge against AI mistakes. After about 2035, the Senior Architect is still working, and still has something to teach. But the AI has eclipsed the Recent Grad in their capabilities, and many of the functions of the firm are handed over to the AI. The Recent Grad loses the opportunity to learn by doing, and by making mistakes. In a sense, their learning stops in 2035. And they cannot jump ahead to some later stage in life, or magically accrue a decade’s of experience overnight.

Their options will be to exit architecture, or evolve into whatever architects eventually become. Let us pray they choose the latter.

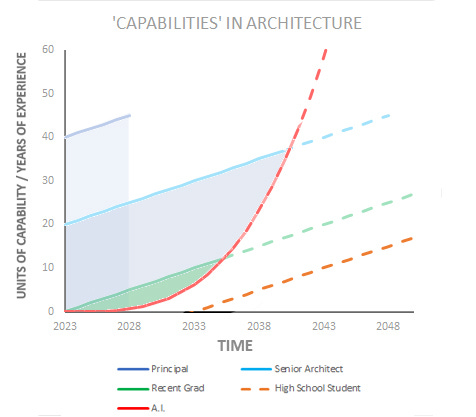

The High School Student

The High School student represents the biggest problem of all for architecture:

Someone who’s entering high school today might enter the profession in 10 years - let’s say 2033. At that time, they’re entering the profession below the capability curve of AI. At that year, the AI has a considerable advantage which will only expand. So anyone who’s a firm principal at that time will face a glaring question: why hire them?

You could make the case that they will bring ‘human’ qualities like creativity and people skills, but creativity and people skills do not an architect make. Yes, an architect needs to have those. But they rest on top of an extensive and hard-fought body of technical knowledge. You could make the case that the high school student can begin learning all that stuff once they enter the profession in 2033, the same way we all did when we entered the profession (for me, 1999). But why? At what? It’s unclear. It wouldn’t make sense for them to stay up all night memorizing the building codes, as I once did. Not when the AI has real time access to every building code on the planet, and can instantly apply them in its generative design process. It would be like my learning how to do logarithms by hand, just to ‘make sure’ that my calculator is doing them correctly.

It’s possible that as architecture evolves with AI, the role of an architect, and her daily duties, shift dramatically and we need even more architects than before. But it won’t be to do what they do now.

What will they do? We may not even reach that question. Concerned parents, like my friend, may steer their children away from architecture merely out of the fear that the employment prospects might be limited. With no clear path about what an architect will do in the age of AI, its possible that some version of my father’s logic takes over, and people generally conclude that it’s a field without future opportunities because AI will overtake and crowd out most architectural labor.

If young, would-be architects feel that there won’t be anything for them to do in the field, they will fulfill their own prophecy by choosing other disciplines. In ten years’ time, we will face a significant pipeline problem. Moreover, anyone coming into the field will be unable to catch the AI in the amassing of technical knowledge that once defined the architectural profession.

It’s unclear what the ramifications of that will be. A few possibilities:

It’s possible that the whole notion of having a single career is lost to history. There will no longer be any value in learning one skill and just getting better and better at it over a lifetime. So a young person exiting college may be an architect for a while, an engineer later, an artist, a legislator, and so forth.

It’s possible that what we once thought of as complex technical skills are simply automated away, much like doing logarithms by hand. Machines sufficiently demonstrate their competency and reliability in those skills, such that we grow sanguine about the fact that we no longer know how to do them. We won’t need the Principal Architect to train the AI or anyone else, because the AI has already learned everything that a single human Principal Architect could teach them. We realize that, grow comfortable with it, and move on.

It’s possible that the age of AI gives rise to a whole new set of complex technical skills that an architect may need to learn and master - the kind that remain beyond the ken of even the most advanced computers. What will those be? I return to the central conclusion of the article: that architects really need to realign and focus on the problems that only human architects can solve. That will surely tell us what skills are necessary to solve them. What are the problems? I don’t know. But I look forward to us all figuring it out together.

1 Moore’s Law was the axiom that guided computer growth for most of the 20th and early 21st century, and postulated that computing power tended to double every two years.

2 “The Law of Accelerating Returns” is an example of double-exponential growth, and popularized by futurist Ray Kurzweil. It has so far anticipated the growth of AI computing power throughout the early 21st century.